Codicology: the history of the structural features of the Codex Sinaiticus

Flavio Marzo

Codex Sinaiticus at the British Library today

The current appearance of Codex Sinaiticus at the British Library is the result of the restoration and binding carried out by Douglas Cockerell (1870–1945) and his son Sydney (Sandy) Cockerell (1906-1987) on the codex in 1935 after its acquisition by the British Museum from the Russian government (December 27th 1933).

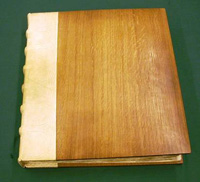

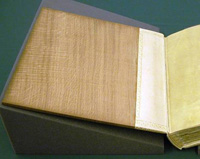

The Manuscript has been bound by Douglas Cockerell in two separated volumes, one for the New Testament (Codex Sinaiticus Testamentum Novum, Additional MS. 43725) and the other for the remaining of the Old Testament (Codex Sinaiticus Testamentum Vetus Additional MS. 43725). They are stored in a wooden box made of English oak lined with light brown goat skin crafted by Douglas Cockerell (picture 2).The book has been sewn on paper and parchment guards in a "meeting guards" sewing structure.

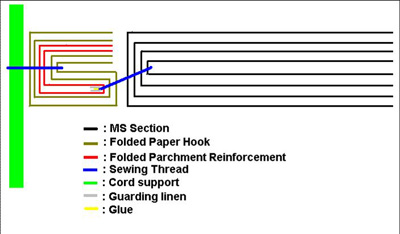

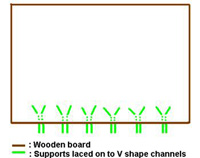

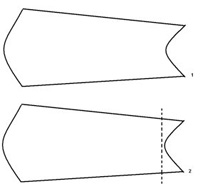

This sewing technique was developed by Douglas Cockerell. He applied it in other famous restoration works and it had a long and very prolific life in the book restoration field. It is made by sewing the sections of the manuscript not directly onto the supports but first onto folded hooks made of layers of paper, parchment and guarding linen and then subsequently on six double cord (hemp) supports ( diagram 1).

|

| 1: Meeting Guard Sewing Diagram |

The absence of a spine lining directly glued to the gutters of the quires creates an almost perfectly flat opening of the text block and makes it the first example of a conservation and reversible book sewing structure. The cord supports are subsequently laced through lightly "cushion shaped" wooden boards made of quarter cut, seasoned English oak (picture 2).

|

|

| 2a: Front board New Testament |

2b: The two parts of the Codex Sinaiticus in the box |

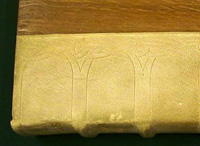

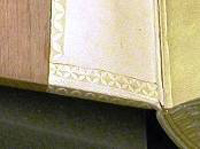

The spine and part of the boards had been covered with white alum tawed cape goat skin (quarter leather binding) and then decorated with a blind "interlaced"[1] decoration on the outside of the boards (picture 3) and on to the inside (squares) and edges of the boards (picture 4).

|

|

| 3: Outside decoration |

4: Inside decoration |

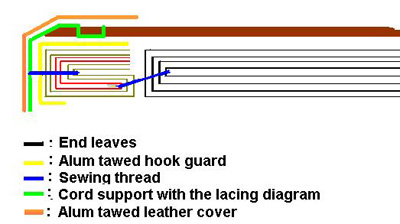

The V shaped lacing channels (picture 7) where the supports are laced through the wooden boards , have been hidden by an alum tawed hook guard/joint attached to the spine fold of the end leaves[2] and then pasted onto the inside board (picture 5).

|

|

| 5: Inside of the front board with the alum tawed hook guard/joint, Old Testament |

6: Lacing and hook guard diagram |

|

| 7: Supports lacing diagram |

The end bands of the Old Testament (picture 8) appear to be sewn on a double trimmed cord cores. The primary sewing with no beads is made with a thread defined by Douglas Cockerell "purse-twist"[3] silk thread, but in his report published in the 1938 he describes them as "headbands worked on single cord"[4]. The New Testament (picture 9), even more inexplicably, has the end band at the head made on a double cords core and the tail one sewn on a single flat trimmed core and there is not obvious reason why the two end bands are made in different ways. Stored as part of Douglas Cockerell's archive in the British Library there is the very detailed correspondence[5] between him and the British Museum committee about all the features and materials used for the re-binding of the Codex and each decision was taken after very careful discussions which make this mismatch all the more inexplicable.

|

|

| 8: New Testament, head |

9: New Testament, tail |

Codex Sinaiticus in the past

There are not many clear signs or indications about the structure of the Codex Sinaiticus during its more then 1600 years of existence.

Codex Sinaiticus is named after the Monastery of Saint Catherine, Mount Sinai, where it was preserved for many centuries.

The first report we have about the Codex is from an Italian scholar called Vitaliano Donati (1717-1762) who saw the book that was presented to him by the monks in the Sinai Monastery where he stopped in 1761 during a journey that he made as assignment by the Italian King Carlo Emanuele III to collect material for the Royal Egyptian Collection, now Egyptian Museum in Torino.[6]

After that leaves and fragments of the Manuscript were taken by Lobegott Friedrich Constantine (von) Tischendorf (1815/1874), a German scholar, on three occasions – in 1844, in 1853 and in 1859 – so that they might be studied and published.

According to Tischendorf, he found about 129 folios of the Codex on his visit to St Catherine's in 1844 of which he took 43 that he presented to Frederick Augustus II, King of Saxony and that are now housed in Leipzig at the Universitäts-Bibliotek.[7]

In the 1845, by the bishop Porphyrius Uspensky other fragments were removed from the Monastery and are now conserved in to the Slatykov-Shchedrin State Public Library, St Petersburg.

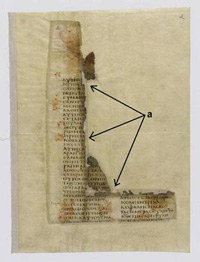

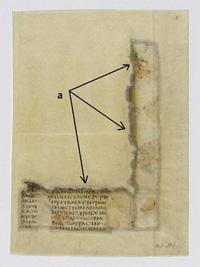

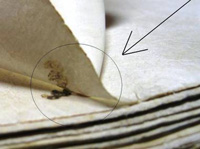

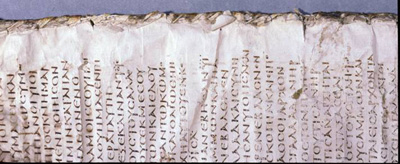

Some of the Russian fragments (like some of the New Finds in the Saint Catherine Monastery)[8] show evidences of folded lines that may suggest they were reused as cover material (picture 10).

|

|

| 10: Repaired fragment, (Greek 259-2r, Greek 259-3r) in St Petersburg, State Public Library |

Evidence of folds suggesting use as cover material are indicated as 'a' |

It is in 1859 that the rest of the book, now cared by the British Library (Volume 1, Old Testament Folios 1-199 and Volume 2 Folios 200-347) was presented to the Tsar Alexander II.

After a few year housed in the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs the manuscript

was then transferred to the Imperial Public Library in Moscow (1867) and this could be the time when the book was housed in the metal box in which it was kept when it was brought to England in 1933 (picture 11 to 15).

Codex Sinaiticus and hypothesis of previous sewing structures

There are several questions which arise from the history of the Codex

Why was the manuscript not bound at the time Tischendorf saw it in the Monastery?

Why was the manuscript not bound until the one given to it by Cockerell in the 20th century? These are important and interesting questions related not only to the structural features of the book but to the history of the use of the Codex.

For the second question there may be an easy answer.

After the Codex was removed from the St. Catherine's Monastery there were many studies carried out on it and all addressed to the textual and palaeographical part of the manuscript.

The first published version of Codex Sinaiticus dated 1862, was a full size facsimile in specially cut type ordered by Tischendorf.

After this edition there is the publication of two photographic facsimiles the first one dated 1911(New Testament) and the other dated 1922 (Old Testament) by Kirsopp Lake, an English biblical scholar (1872-1946).

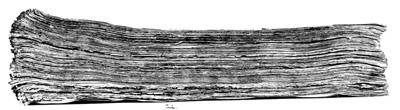

This may be the reason why the manuscript was dis-bound and kept unbound, to allow for an easier consultation and reproduction of the text for all these different publications. Also, the fact that the book was kept in a metal box (pictures 11 to 15) specially made for the Codex itself suggests an intention to keep it unbound for a quite long time.

|

|

| 11: Spine |

12: Front |

|

|

| 13: Back |

14: Head and front edges |

|

| 15: Open tin box with the vegetable fibres wrap that were used to protect the codex leaves during the move from Russia |

In 1938 the British Museum published a study of Codex Sinaiticus where Douglas Cockerell added the complete report of his "conservation" work.

Douglas Cockerell's contribution to the emerging field of book conservation is indisputable; he established possibly for the first time in Codex Sinaiticus condition report, a model for specifications and documentation of vellum text rebinding. Also he pointed out that the good conservation of a book is due not only to the quality of the binding but related to the environment where the book is stored.[9]

In his report Douglas Cockerell gives interesting and useful information about the unbound Codex. He removed many fragments of thread from the gutter of the sections, many of these threads coming from repairs made on the gutters (overcasting sewing) and some that he assigned to previous sewing,[10] some of these are now housed in a bound book kept in the British Library as part of his archive.[11]

He identified at least two different kinds of thread that he ascribes to two different sewing structures.[12]

He is assuming that the "second" and last sewing was made in the work shop in the Saint Catherine's Monastery, after the first visit of Tischendorf but in some way never finished,[13] this was just assumed because there were no sign of board attachments that were may be removed when the manuscript was took to Russia.

What it is possible to say from the consistency and continuity of the line of sewing station marks on the spine, visible in the black and white photograph taken by Douglas Cockerell before the treatments (picture 26) is that the Codex was, at least for the last part of its life before arriving to Russia, bound together.

The pictures he took before the treatments are the only useful evidence we have to reconstruct and suggest possible previous sewing structures. In the report made during the present conservation project we recorded all the visible evidence of features related to previous sewing structures or repairs, we recorded location and nature[14] of sewing stations and pre-Cockerell repairs. Unfortunately the careful repairs made by Douglas Cockerell hided all these features at the point that was impossible to collect significant information from the inside of the text block.

Douglas Cockerell himself underlines the presence of blade marks along the fore-edge due to very crude edge trimming; they are predominantly towards the end but are evident throughout the text block, which can only be done when the two text blocks were sewn together and this is the only visible evidence of a trimming of the edges.

|

16: Trimming blade marks on the fore edge of the New Testament |

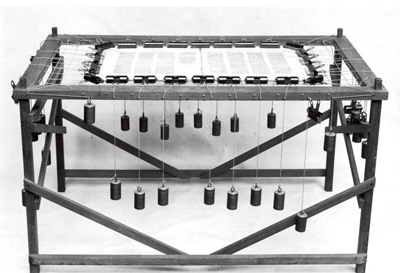

The dimensions of the Codex Sinaiticus are impressive and it is very hard to imagine them been much bigger then what we can see today. It is important to say that the restoration work done by Douglas Cockerell did not, even after the use of the starching table (picture 17) for flatting the sheets, changed the dimension of the leaves of the Codex.

|

| 17: Stretching table (British Library, Add. 43725* 2409C f.27) |

The dimension of the pages vary from 386 mm of page 113 in the Old Testament to a minimum of 374mm of page 2 of the Old Testament again and due the last crude trimming of the fore edge the leaves near the centre are now broader than those at the beginning.

The thickness of the leaves of the Manuscript goes from 0,07micron of page 6 in the Old Testament to a maximum of 0, 25 micron of page 41 of the Old Testament.

The Codex fortunately still retains some untrimmed corners, one at page 171 of the Old Testament (B.L. numeration) and another one at page 229 of the New Testament. This last one shows that the book was trimmed at the head edge and on the fore-edge for about 6mm.

At its creation the text block was composed by around 730 pages, more than double the actual remaining pages (347), sewn together and covered possibly with thick wooden boards may be covered by leather. An impressive, powerful object; a book, that in the 4th century was not such a common object at all, that was the embodiment of the Divine and the Constantinian earthly power.

|

|

| 18a: Untrimmed corner in Quire 69, 4r (British Library f.171r) |

18a: Untrimmed corner in Quire 76, 6r (British Library f.229r) |

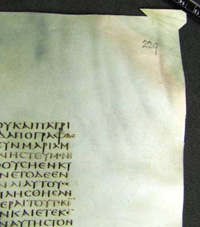

Interestingly the text block still has what would be called the original fasciculation at the top left corner of many of the first page of the sections, this is a very small and close to the edges writing and usually, after the binding of a manuscript, was easily trimmed away.

This could indicate again that the edges, although certainly trimmed once, may not have been trimmed more than that.

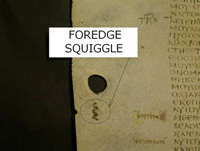

Another interesting feature related with the trimming of the fore-edge is the fore-edge "squiggle" (picture 19a-b).

This is an ink mark traced in the middle of each section almost in the centre of the fore edge of the pages, between the areas f and g in the reference grid used for the location of the areas on the pages.[15]

|

|

| 19a: Fore edge squiggle in Quire 40, 5v (British Library f.25v) |

19b: Fore edge squiggle in Quire 40, 6r (British Library f.26r) |

The "squiggle" was made by tracing it with a pen (possibly made by a pointed bamboo stick, "calamus") and ink on the recto of the right part of each central bifolium of the sections and then closing the previous page to create an off-set on its verso (picture 19b).

It could be possible to relate this feature with the process of binding the book, considering that this ink mark makes it possible to easily find the exact centre of the quire without completely opening it.

Also these marks could be made by the scribes to identify the sections been definitively checked and ready to be bound.

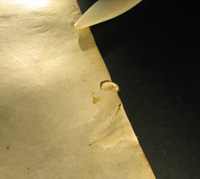

This mark is always located in the middle of the section which means that it has no correlation with the content of the book, by contrast there are bookmarks made with loops of thread and traces of glued leather (picture 20), which could be the remaining of leather strips used as references to highlight peculiar and important parts of the text.

|

|

| 20a: Fore edge mark: thread and leather remaining in Quire 43, 1r (British Library f.42) |

20b: Fore edge mark: thread and leather remaining in Quire 64, 1r (British Library f.128) |

If this is a feature related to the making of the sewing it was intended to be visible only during its realisation and so removable when the trimming of the fore-edge was done.

The new sewing done by Douglas Cockerell (stub guard sewing) creates a flat spine; this pushed out the fore edge of the text blocks giving it an unusual shape (pictures 22 and 23). The fore-edges of the two volumes, when virtually joint, is strongly rounded (convex).This can be explained because the fore edge of the Codex was trimmed when the bound book was having a pronounced swelling of the spine. This could be explained by an excessive thickness of the sewing thread, which can caused this kind of peculiar feature.

Cockerell in his report made a drawing where he hypothesized it too (picture 20).

|

21: Cockerell's diagram of the "original" binding

(British Library, Add. 43725* 2409C f.20)

|

Moreover, looking at the shape of the fore edges today, when joined, it appears clear that there is a missing part of the text block; it looks like a big part of the convex curve is missing (picture 24) and this could suggests that the trimming of the edges was done when the manuscript was complete and bound with the now missing part of the Old Testament (first sewing) and never again.

|

|

| 22: New Testament fore-edge |

23: Old Testament fore-edge |

|

|

| 24:

1: Profile from head or tail of the book after the sewing with natural round spine with swell due the thickness of the thread;

2: Fore edge trimming

|

3: Flat fore edge;

4: Actual flat spine shape with change of the profile on the fore edge with the missing part

|

In his report Douglas Cockerell described the "last sewing" as a supported sewing.

There is no evidence from his report or the collected fragments of threads[16] (picture 26) of any remaining of cords or other material that could be recognised as supports.

It is very difficult to say anything for certain as the current bound state of the Codex does not give the opportunity to check the spine and to recognise visible signs of sewing stations but it is possible to add some more hypotheses.

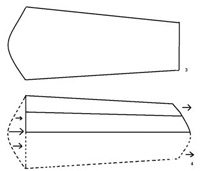

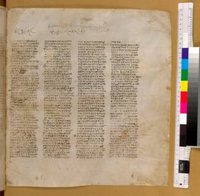

In Douglas Cockerell's report there are some interesting pictures of the spine with 4 irregular lines of marks on the outer side of the gutter, presumably, corresponding with the last sewing stations (pictures 27 and 28).

|

| 25: Tail edge of the complete Text block before the Douglas Cockerell's new binding

(British Library, Add. 43725* 2409C f.9)

|

|

| 26: Remains of sewing thread from the unbound Codex

(British Library, Add. 43725* 2409C f.3)

|

As Douglas Cockerell pointed in his report they are very irregular, especially the first and the last.

There is much evidence of marks on the spine that could be considered other sewing stations but it is very difficult imagine a supported structure (cords or leather supports) with such irregular distribution. It is more reasonable to imagine an unsupported sewing done without a lot of care, where the tension of the thread during the sewing causes the strong skewing of the first and last sewing station. It is possible to further hypothesize that the reason for such irregularity in the sewing station lines was due to the use for the binding of reused wooden boards with set holes for the start of the sewing.

Douglas Cockerell says in his report "the swelling caused by the overcasting and the very thick double thread must have made a floppy volume with an unmanageable and shapeless spine"[17] and it is possible to find in many example of survive Byzantine structures a similar feature where the excessive thickness of the thread increase the swelling of the spine but also it is been hypothesized that the overcasting sewing done with strips of parchment, still visible in the Saint Catherine's untouched section (picture 33), was may be part of the original sewing structure. It was made to attach single sheets of parchment, instead of bifolia, to the quires and this could be another obvious reason for the over-swelling on the spine.

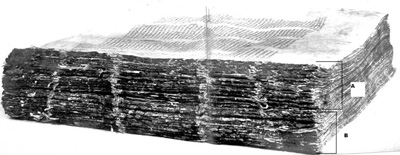

The peculiar shape of the text block is another interesting feature; it shows a sort of "division" in half of the text block (pictures 25).

|

| 27: A: Old Testament; B: New Testament (British Library, Add. 43725* 2409C f.6)

|

|

| 28: Spine of the text block with evidence of four sewing stations

(British Library, Add. 43725* 2409C f.10)

|

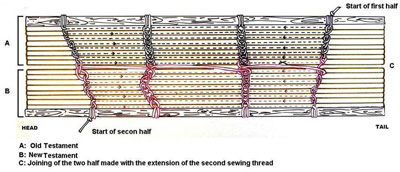

This visual evidence could possibly suggest that the text was originally sewn in two parts, as was many time suggested, as it is today, but at equally could resemble a kind of Byzantine sewing structure made by sewing the text block in two separated halves.

This sewing is made sewing one half of the text block starting the sewing from the upper board and the other from the lower one, then the two distinct text blocks are joined together with a separated sewing thread or with the extension of the second half sewing thread in the centre of the spine (picture 29). In this reconstruction the two half of the text block are joined in the middle by the extended thread of the lower half that is connecting them through in a "figure of eight" stitches. These stitches could be identified with what D. Cockerell calls "loops still remaining on the thread in quire 70"[18] and that he points as evidence for the passage of the thread around the hypothetical supports.

|

|

|

| 29: Possible reconstruction of the last sewing structure of the Codex Sinaiticus -

"Byzantine sewing structure in two halves"

|

The dummy of this sewing structure (picture 30) recreates exactly the same double round spine shape.

|

|

| 30: Dummy of the two halves |

'Byzantine sewing structure' |

This kind of sewing structure was first studied and described by Guy Petherbridge[19] in the Patmos Monastery Library and by Konstantinos Houlis[20].

It is beside reasonable to imagine such sewing structure made in the work shop of the Saint Catherine's monastery where we know existed a book binding studio[21] and where the community of monks is always been composed of Greek monks who brought their own culture and crafts to Egypt.

The Byzantine sewing structure is characterized by a link-stitch sewing on more then two sewing stations, spine lining of cloth extending to the outer face of the boards, back with no visible supports, wooden boards usually with grooved V shaped edges and attached to the text block through the passage of the sewing thread, no squares and end bands extended on the edges of the boards.

Many of these features could change slightly depending on the time and place where the book was bound and can not be positively identified from the picture of the unbound text block of Codex Sinaiticus.

The geographical borders and the chronology are extremely wide; the influence of the Byzantine Empire persisted long after the falling of Constantinople in1453, manufacture of all kind of crafts spread over a vast geographical area comprised of countries like Armenia, Georgia, Syria, islands of eastern-Mediterranean such as Cyprus or Crete and Greece and then the Saint Catherine's monastery with its Community in the Egyptian desert.

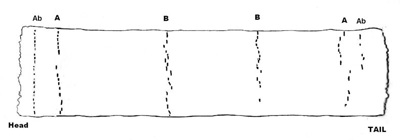

It is also possible to see on the picture of the un-sewn text block taken by Douglas Cockerell, some marks that could possibly be identified with the passage of the thread for the sewing of the end bands (picture 31Ab) or may be the sewing stations of a previous sewing structure (picture 31a/b).

|

|

| 31: Marks of the sewing stations for the end bands and sewing stations from previous structure. |

What is more difficult to understand is why Tischendorf describe finding the Codex split in many different locations in the Monastery. Could be possible that the Codex, at the time the German scholar saw it, was kept unbound for some reason?

It could be that the Manuscript, considering the importance of its age and its sacredness was used in the context of a monk community as a sort of "master copy", a reference for other manuscripts that were produced by the monks for internal use and for to be sent to other sites.

Interesting evidence that could support this theory is the good condition of the manuscript pages.

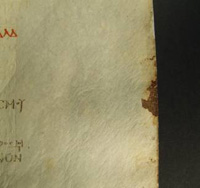

In Cockerell's report he mentions that the text block was heavily repaired along the spine suggesting that it was may be bound and unbound many times but with not equal amount of damages on the surface of the pages. Different kind of stitches and sewing were recognisable along the gutter of the sections, overcasting sewing with thread or parchment strips and different remaining of the sewing threads (picture 32) that are still visible on the fragments in Saint Catherine's Monastery today.

Comparing the condition of the parchment on the text area with the condition of the spine, still visible today on the untouched new finds in the St.Catherine's Monastery (picture 33) it is possible to assume that the use of the book has been quite peculiar.

|

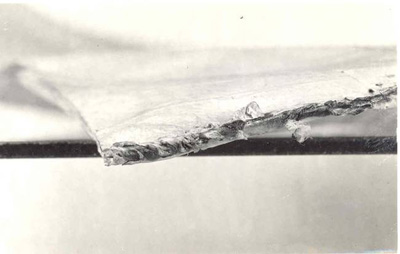

| 32: Detail of overcasting sewing before Douglas Cockerell's restoration

(British Library, Add. 43725* 2409C)

|

|

| 33: Detail of overcasting sewing (thread and parchment) on the New Finds, Saint Catherine's Monastery[22] |

A liturgical manuscript used for example in a church, usually shows much more damages on the surface, like strong handling marks or drops of wax and others like these but even with many repairs to the spine, sign of use, the Codex Sinaiticus does not bear an equal deterioration of the textual area, moreover sometimes it is possible to find stains on a page that are not showing visible offset on the following one, like on page 41 verso of the Old Testament compared to the following one on the recto and on page 73 verso compared to 74 recto and all these features could possibly support the theory of a storage of the manuscript split and may be bound in different parts and used in different places possibly to be copied by different monks at the same time.

|

|

| 34: Quire 42, 8v (British Library f.41v) |

35: Quire 43, 1r (British Library f.42r) |

Conclusions

- The restoration of the Codex carried out by Douglas Cockerell and his son saved many of the original features of the manuscript (such as book mark evidences remaining loops of threads and leather accretions on the fore edges).

- Cockerell's accurate documentation made itt possible to make hypotheses about previous sewing structures.

- It is now possible to say that the Codex Sinaiticus was never bound in two volumes as it is now.

- The text block edges were probably not trimmed more then once.

- This was not done during the last sewing before the present one.

- Codex Sinaiticus was kept unbound at least for the last part of its life before coming to England.

- The previous binding was in a "Byzantine" style and that it was never sewn on supports as suggested by Douglas Cockerell.

Future research

- In order to have a better understanding about the manuscript's very complex and rich use (possible storage and its separated parts or unbound) a more accurate mapping of the stains could be extremely useful.

References

[1] D. Cockerell, Scribes and correctors of the Codex Sinaiticus, London: British Museum, 1938, p. 86.

[2] "one leaf of grained vellum and two leaves of plain, slightly stained vellum"(Cockerell, Scribes and correctors, p. 86).

[3] Cockerell, Scribes and correctors, p. 86.

[4] Cockerell, Scribes and correctors, p. 86.

[5] Additional MS 43725, Cockerell Archive.

[6] "In questo monastero ritrovai una quantità grandissima di codici membranacei… ve ne sono alcuni che mi sembravano anteriori al settimo secolo, ed in ispecie una Bibbia in membrane bellissime, assai grandi, sottili, e quadre, scritta in carattere rotondo e belissimo" (G. Lumbroso, Atti della R. Accademia dei Lincei, 1879, p. 501). Cf. http://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vitaliano_Donati

[7] Codex Frederico Augustanus, Ms gr.1.

[8] Twelve leaves and forty fragments remain at Saint Catherine's Monastery, recovered by the monks from the northern wall of the monastery in June 1975.

[9] "The reasons that have led to the production in modern times of bindings that fail to last for a reasonable time are twofold. The materials are badly selected or prepared, and the methods of binding are faulty. Another factor in the decay of bindings, both old and new, is the bad conditions under which they are often kept." (D. Cockerell, Bookbinding and the Care of Books, New York, 1902.

[10] Cockerell, Scribes and correctors, p. 82.

[11] Additional MS 43725, pages 1-3.

[12] "There is conclusive evidence of at least two bindings. The first and probably the original binding was sewn by single threads of loosely twisted hemp. Only a few fragments of this have survived and there is not enough evidence to show how the leaves were sewn … The quires in the later binding were sewn with thick double hempen threads, some of witch were twisted together and some straight. This thread is indistinguishable in texture from the remaining fragments of the earlier single thread sewing. Some fragments from lightly twisted flax thread were also found, in one case knotted to the hempen thread of the later sewing." (Cockerell, Scribes and correctors, p. 82-83.

[13] "It is quite possible that this later binding was never actually completed." (Cockerell, Scribes and correctors, p. 83).

[14] See reference grid in the condition report form.

[15] See reference grid in the condition report form.

[16] Add. 43725* 2409C, Paper Related to Codex Sinaiticus.

[17] Cockerell, Scribes and correctors, p. 83.

[18] Cockerell, Scribes and correctors, p. 83.

[19]Guy Petherbridge, "Sewing Structures and Materials: A Study in the Examination and Documentation of Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Bookbindings", Paleografia e codicologia greca: Atti del secondo Colloquio internazionale (Berlino-Wolfenbuttel 17-21 ottobre 1983), eds. Dieter Harlfinger and Giancarlo Prato, Alexandria: Edizioni dell Orso, 1991, vol. 1, pp. 363-408, vol. 2, 201-9.

[20] Konstantinos Houlis, "A Research on Structural Elements of Byzantine Bookbinding", Ancient and Medieval Book Materials and Techniques (Erice, 18-25 settembre 1992), eds. Marilena Maniaci and Paola F. Munafo, Studi e Testi 358, Vatican City: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, 1993, vol. 2, pp. 239-68.

[21] N. Sarris, Saint Catherine' Foundation Bulletin, 2009.

[22] Codex Sinaiticus 008.12f.f.v, New Finds Saint Catherine's Monastery.